|

MEDICINE |

Written by Ghazi M. Al-Hachim, PhD

![]() en

centuries ago, the Muslim Empire was at its zenith; its various

parts vying with one another in producing intellectual giants in

every branch of art and science. Many of these great men

practiced in the field of the healing arts, and their works

became the basis on which modern medicine has been founded.

Without them, we would not have seen the progress that we take

for granted today in various branches of health and medicine all

over the world. These great men of thought were active in many

of the branches of medicine that are practiced today, such as

ophthalmology, anatomy, internal medicine, psychiatry and

preventive medicine. It is only nowadays that western doctors

are beginning to acknowledge the debt that is owed to these

early Muslim scholars.

en

centuries ago, the Muslim Empire was at its zenith; its various

parts vying with one another in producing intellectual giants in

every branch of art and science. Many of these great men

practiced in the field of the healing arts, and their works

became the basis on which modern medicine has been founded.

Without them, we would not have seen the progress that we take

for granted today in various branches of health and medicine all

over the world. These great men of thought were active in many

of the branches of medicine that are practiced today, such as

ophthalmology, anatomy, internal medicine, psychiatry and

preventive medicine. It is only nowadays that western doctors

are beginning to acknowledge the debt that is owed to these

early Muslim scholars.

Ibn Al-Khatib (1313 - 1374)

Ibn Al-Khatib was one of the earliest of these scholars. He lived in Granada, Spain and his most famous work is on the theory of infection:

'There are those who ask, 'How can we allow for the possibility of infection?'

We reply that the existence of contagion is established by experience, investigation, the evidence of the senses and trustworthy reports. These facts create a sound argument, so that the fact of infection becomes clear to the investigator, who notices how those in contact with afflicted people get the disease, whereas those not in contact remain safe. The investigator also sees how transmission occurs through clothing, cups and earrings.'

Ali

Ibn Rabban Al-Tabari (838 - 870)

Ali

Ibn Rabban Al-Tabari (838 - 870)

Ali Ibn Rabban Al-Tabari wrote Firdous al-Hikmat, the first ever medical encyclopedia that incorporated all the branches of medical science. This encyclopaedia dealt with the ideology of medicine; detailed the organs of the human body, gave rules for keeping good health and gave a comprehensive account of certain muscular diseases. It contained advice on preventative and curative diets. It also held accounts of disease causation; diseases of the head and brain; eye, nose, ear, mouth and teeth; muscular diseases; diseases of the chest, throat and lungs; the abdomen, liver, gallbladder, spleen and intestines; fever; and diagnostics through the examination of pulse and urine.

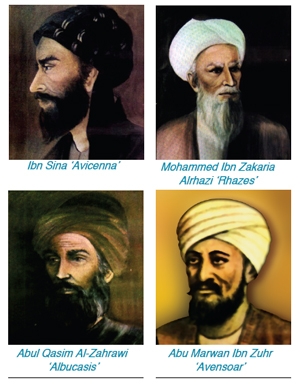

Mohammed Ibn Zakaria Alrhazi 'Rhazes' (841-926)

Mohammed Ibn Zakaria Alrhazi was a Hakim; an alchemist and a philosopher. In medicine, his contributions were so significant that they can only be compared to those of Ibn Sina. Some of his works in medicine, eg: Kitab al-Mansoori, Al-Hawi, Kitab al-Mulooki and Kitab al-Judari wa al-Hasabah, earned him everlasting fame. Kitab al-Mansuri, which was translated into Latin in the l5th century AD, was in ten volumes and dealt exhaustively with Graeco-Arab medicine. Some of its volumes were published separately in Europe. Al-Judari wal Hasabah was the first treatise on smallpox, measles, scarlet fever and chicken-pox, and is largely based on Razi's original contributions. It was translated into various European languages, and was the first to describe clinical differences between chicken-pox and measles so vividly that nothing since has been added. His book on children's diseases is regarded as the first of its kind.

Abul Qasim Al-Zahrawi 'Albucasis' (936-1013)

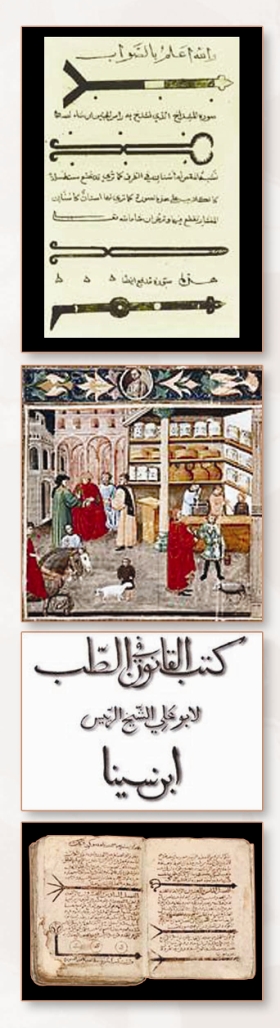

He is best known for his breakthroughs in surgery as well as for his famous Medical Encyclopedia called Al-Tasrif - thirty volumes covering different aspects of medical science. This contained three books on surgery, which describe in detail various surgical procedures including cauterisation, amputation in the cases of gangrene and cancer, lithotomy, craniotomy, removal of stones from the bladder, dissection, midwifery, and surgery of the eye, ear and throat. He perfected several delicate operations, including amputation, and instrumental delivery of the foetus in childbirth.

Al-Tasrif was first translated by Gherardo de Cremona into Latin in the Middle Ages. The book contains around one hundred diagrams and illustrations of surgical instruments, in use or developed by him, and comprised a part of the medical curriculum in European countries for many centuries.

Al-Zahravi was also a dental expert and his book contains sketches of various instruments used, in addition to a description of various dental operations. He discussed how to rectify non-aligned teeth, and how to prepare artificial teeth to replace them.

Ibn Sina 'Avicenna' (980-1073)

Ibn Sina wrote the Qanun fi Al-Tibb (The Canon of Medicine), translated into Latin by Gherardo de Cremona, and edited more than fifteen times in Latin. It formed half of the medical curriculum of European universities up to the end of the fifteenth century. The Qanun fi al-Tibb is an immense encyclopaedia of medicine of over a million words, and surveying all medical knowledge available from Muslim and other sources. The book is also rich with the author's original contributions, including such advances as recognition of the contagious nature of phthisis and tuberculosis; distribution of diseases by water and soil, and interaction between psychology and health.

In addition to describing pharmacological methods, the book described 760 drugs and became the most authentic materia medica of the era. Ibn Sina was the first to recognise meningitis, to differentiate pleurisy from 'simple inflammation of the mediastinum and abscess of the upper surface of the liver'. He also distinguished between obstructive, haemolytic and hepatic jaundice and made rich contributions to anatomy, gynaecology and child health.

Ibn Sina originated the idea of the use of oral anesthetics, including opium, mandragora, poppy, hemlock, hyoscyamus, deadly nightshade (belladonna), lettuce seed, and snow, or ice-cold water.

Ibn Zuhr 'Avensoar' (1113-1162)

Ibn Zuhr of Seville was an outstanding clinician. His most celebrated work was Kitab al-Taisir fi al-Mudawat wa al-Tadbir (Book of Simplification concerning Therapeutics and Diet), a book on clinical medicine in which he described many diseases for the first time. The book was translated into Latin by Paravicius in 1281.

Ibn Zuhr was the first to describe serious pericarditis, also scabies, the itch mite and may thus be regarded as the first parasitologist. Likewise, he prescribed tracheotomy and direct feeding through the gullet and rectum in cases where normal feeding was not possible. He also gave clinical descriptions of mediastinal tumours, intestinal phthisis and inflammation of the middle ear.

Ibn Al-Nafies 'Annafis' (1210-1288)

Ibn Al-Nafies of Damascus made major contributions to medicine both through his detailed commentaries on early works, and his discovery of the blood's circulatory system, only re-discovered three centuries later. He was the first to correctly describe the constitution of the lungs and gave a description of the bronchi and the interaction of air and blood between the vessels of the human body.

Physical health

Islam not only established a healthy society but encouraged Muslims and those who came in contact with them to pay attention to physical health. This was the basis for establishing hygienic rules as stated in the two sources of Islamic Law, the Holy Qur'an and the Prophet's (PbuH) Sunna.

Hospitals

The development of efficient hospitals was an outstanding contribution of Islamic medicine. Hospitals served all citizens free without any regard to their colour, religion, sex, age or social status. The hospitals were run by the government and their directors were physicians. It was chiefly in the humaneness of patient care, however, that the hospitals of Islam excelled. Near the wards of those afflicted with fever, fountains cooled the air; the insane were treated with gentleness; and at night music and storytelling soothed the patients.

Location

Before establishing any hospital, Muslims looked for a healthy convenient location. Before choosing a site for Baghdad hospital, Alrhazi hung pieces of fresh meat in various Baghdadi neighbourhoods and said that the best neighbourhood to establish the hospital in would be the one where the piece of meat would rot slower than any of the other pieces.

Hospital organisation and administration

Europeans have learned a lot from Muslim hospitals, which were very advanced in terms of organisation and administration. There were outpatient and inpatient departments. Some hospitals had waiting rooms for visitors and patients and female nurses. Hospitals also had housing for students and house-staff. On-site pharmacies dispensed free drugs to patients.

Hospitals also had their own conference rooms and expensive libraries containing the most up-to-date books - 80,000 volumes (Baghdad) to 3,000,000 (Tripoli). Hospitals kept records of patients and their medical care, as diagnostics were very important, with notes being kept on patients' past diseases and treatments.

Separate wards

Hospitals had separate wards for male patients and female patients; each with a nursing staff and porters of the same sex as the patients. Muslim hospitals gave every patient their own clothing, to avoid infection, and patients also had unlimited water supplies and bathing facilities. Different diseases such as fever, wounds, infections, mania, eye conditions, colds, diarrhoea, and gynaecological disorders were allocated different wards.

Convalescents had separate sections. There were special hospitals for certain diseases such as leprosy, fever and mental disorders. At the Tulun hospital, on admission, the patients were given special robes, while their clothes, money, and valuables were stored until the time of their discharge.

On discharge, each patient received five gold pieces to support himself until he could return to work.

Only qualified and licensed physicians were allowed by law to practice medicine. The hospitals were also educational institutes for the teaching of medical students.

Licensing of Physicians

In Baghdad in 931 AD, Caliph Al-Muqtadir learned that a patient had died as the result of a physician's error. Thereupon he ordered his chief physician, Sinan Ibn Thabit Ibn Qurrah to test all those who practiced healing. In the first year, more than 860 were tested in Baghdad alone. From that time on, licensing examinations were required and administered in various places.

Licensing Boards were set up under a government official called Muhtasib or inspector general, who also inspected the weights and measures of traders and pharmacists. Pharmacists were employed as inspectors to inspect drugs and maintain quality control of drugs sold in a pharmacy or apothecary. The chief physician gave oral and practical examinations, and if the young physician was successful, the Muhtasib administered an ethical oath of conduct and issued a license.

A debt

Many of the works of Muslim physicians such as Ibn Sina and Alrhazi were translated into different European languages for use in research and teaching. Those works continued to be used till the eighteenth century and prepared the west for modern developments in medicine. The University of Paris keeps in the College of Medicine two large coloured pictures, one of Alrhazi and the other of Ibn Sina. The University of Princeton in the USA called the largest of its buildings after Alrhazi, in appreciation of his work.

Historians say that even in 1917,

the University of Louvain relied on the works of Alrhazi and Ibn

Sina. Many universities required their students to study the

great works of Alrhazi and Ibn Sina as partial requirements for

receiving a degree in medicine

![]()