|

ARTS AND CRAFTS |

Written by Ron Toft

Photographs courtesy of The Natural History Museum, England

![]() he

mysterious black substance was first discovered in about 1500 AD on Seathwaite Fell Mountain, Borrowdale, near Keswick, in England's

picturesque Lake District. Initially it was believed that the soft,

rock-like substance was coal, but it didn't burn. It proved to be an

ideal medium, however, for marking sheep and also had useful

medicinal properties.

he

mysterious black substance was first discovered in about 1500 AD on Seathwaite Fell Mountain, Borrowdale, near Keswick, in England's

picturesque Lake District. Initially it was believed that the soft,

rock-like substance was coal, but it didn't burn. It proved to be an

ideal medium, however, for marking sheep and also had useful

medicinal properties.

Black lead

During Queen Elizabeth I's reign, 1558 - 1603, this unusual substance - known as wad, black lead or plumbago, was used to make moulds for cannonballs; lumps extracted from Seathwaite Fell being transported to the Tower of London in armed stagecoaches.

A drawing and writing material

Wad was also in demand as a

drawing and writing material. In fact, it became so highly prized

that local people regularly scrambled over spoil heaps in the hope

of finding fragments they could sell to Flemish traders. Such pieces

were then transported across the fells on packhorses to waiting

ships. There were many battles over it around Keswick, one notorious

gang stealing the equivalent of £150,000 worth of the black gold

annually.

Wad was also in demand as a

drawing and writing material. In fact, it became so highly prized

that local people regularly scrambled over spoil heaps in the hope

of finding fragments they could sell to Flemish traders. Such pieces

were then transported across the fells on packhorses to waiting

ships. There were many battles over it around Keswick, one notorious

gang stealing the equivalent of £150,000 worth of the black gold

annually.

Seathwaite Fell

Today this valuable and versatile mineral is universally known as graphite - one of only two naturally occurring forms of pure carbon. The chance discovery of graphite on Seathwaite Fell led to the creation of the world's first pencil industry in the Lake District. Long ago, artists wrapped graphite in pieces of sheepskin, or wrapped string around them. It was the Italians who developed the first wooden holder and following this, generations of Keswick families made pencils by hand at home.

Jacques Conte

Jacques Conte revolutionised the pencil-making process in 1795 by kiln-firing a mixture of inferior shale graphite with clay. This proved to be a timely development, for supplies of the very pure Lake District 'lump' graphite were dwindling by 1833. Borrowdale Mine finally closed in 1890. After that, supplies of shale graphite were imported. The first known pencil factory was established in Keswick in 1832 by A. Wren. By 1851, there were four such concerns in Keswick. Wren's factory, which has changed hands several times, is now run by the world famous Cumberland Pencil Company, a division of US-owned Acco UK Ltd.

Three-quarters of a million pencils

Every week, the firm makes three-quarters of a million pencils of various types for diverse customers globally. The story of graphite mining and pencil making in the Lake District is told in the company's Cumberland Pencil Museum.

The museum

Visitors enter a replica of Borrowdale Mine where men dug and hacked out graphite. Each miner wore a leather skull cap or bowler hat, clogs and moleskin trousers covered in sacking. The 'mine' leads into the museum proper where displays describe everything from the raw materials used to the different processes involved in making both ordinary 'lead' pencils and coloured ones. Biggest of all the exhibits is a 7.9 metre long cadmium yellow pencil weighing around 445 kilograms. It was completed on 28 May 2001 by the Cumberland factory and is officially the world's largest coloured pencil.

Absolute secrecy

Arguably the most fascinating pencils on display are three seemingly-normal green ones - part of a very special James Bond-like range produced in absolute secrecy during World War II. Hidden within a specially drilled cavity in the barrel was an ultra-thin, tightly rolled map of enemy territory. Cunningly concealed under the eraser was a tiny compass. A code on the outside of the pencil indicated the region covered by the map. These pencils were issued to Bomber Command aircrews as part of their escape kit.

The Snowman

Among the many other exhibits in the museum are shaping, painting and stamping machinery, woodworking equipment, British pen nibs (the factory was formerly owned by British Pens Ltd which made disposable pen nibs), early Cumberland pencils and packaging materials and a video room. Screened at regular intervals in the latter is a short film about pencil-making and a clip from The Snowman, the film based on Raymond Briggs' book of the same name. Briggs used Cumberland pencils to generate several thousand animated drawings for the highly acclaimed cartoon production.

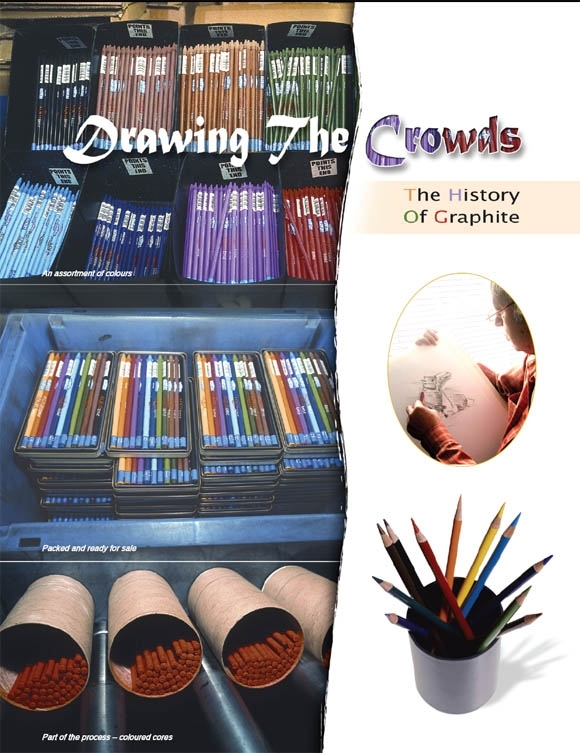

Degrees of hardness

Graphite cores or strips, which are made by mixing graphite powder with clay, are fired in a furnace before being sandwiched between two wooden slats, glued together and cut to form individual pencils. Graphite pencils are produced in 20 degrees of hardness, from a fine 9H to a soft and smudgy 9B. Hardness is determined by the amount of clay present. The harder a pencil, the more clay it contains. Coloured cores or strips, which are made by mixing organic or chemical pigments with clay, are dried slowly in an oven and then soaked in wax to soften their consistency.

Sri Lanka, Korea and China

The Cumberland Pencil Company imports processed graphite from a number of countries, including Sri Lanka, Korea and China. It uses two types of clay - English china clay and German ball clay. Coloured pigments are obtained from a variety of sources. Wood for pencil barrels comes from sustainably-grown Californian incense cedars.

The products

Many different products are made in Keswick under the Derwent brand name to meet the varying needs and standards of amateurs and professionals alike. These include natural graphite blocks, compressed charcoal sticks, coloured pencils, pastel pencils, metallic pencils and water-soluble sticks. Most popular of all is the Artists range of 120 coloured pencils. At the premium end of the market is the Signature collection of 60 light-fast or fade-resistant coloured pencils and 40 watercolour pencils made from the purest pigments and finest raw materials.

'There are only so many colours you can put into pencil sets before they start looking very much the same,' said production manager Clive Farrar who has worked for the Cumberland Pencil Company since the late 1980s.

'The 120 in our Artists range is more than enough. Most of our other ranges are limited to 72 colours. Colours can be mixed quite easily on paper, so customers who buy our products actually have an infinite range at their disposal.'

A

unique set of colours

A

unique set of colours

Cumberland, like other pencil manufacturers, produces a unique set of colours by blending various pigments. 'Aquamarine blue means one colour to you and an entirely different one to me, because the description is non-specific,' Clive explained. 'If, however, we were both talking about Derwent spectrum blue, for example, we would be referring to a specific colour which has been in production here for half-a-century or more.'

Popularity

Pencil colours fluctuate in popularity - sometimes for no apparent reason. 'There was a time when royal blue was very popular as a spare pencil. If red and white - the other colours of the Union Jack flag - had been equally as popular, we would have understood what was going on. But they weren't. Sales of royal blue went through the roof, typically three or four years' turnover being achieved in just three or four months.'

Sepia work

One of Cumberland's niche ranges caters for artists with a penchant for sepia work. 'We introduced a limited range of six warm earthy colours, like brown ochre and terracotta, but customers asked if we could add a bit more variety, so we are currently developing a range of 24 colours which will include not only more sepia tones but also some greys and very pale blues.'

Graphite products

Although coloured pencils now account for around 80 per cent of Cumberland's output, the company is still very much committed to graphite products which are especially popular with people who sketch or draw in the field.

Highly automated

Pencil making was once a labour-intensive industry. Nowadays, however, many elements of the manufacturing process are highly automated. 'Over the years, improvements to machinery have speeded up production and reduced the workforce. What used to take weeks in the factory is now completed in only a couple of days,'explains Clive Farrar.

Computer technology

Cumberland currently employs 85 people, 56 of whom are directly involved in pencil making. Many have worked for the company for over ten years. The growing use of computer technology and on-screen graphic design work has had little effect on Cumberland and its products. 'People who use computers for graphic design purposes usually don't touch pencils,' Clive told me. 'Most of our customers are people who either draw and paint as a leisure activity or as a profession. 'Some of the works produced by one of our customers, a guy who uses pastel pencils, sell for tens of thousands of pounds each. The fact that our products earn him a very substantial living gives me real job satisfaction.'

New products and new ideas

Around 65 per cent of the Cumberland Pencil Company's products are exported, the biggest markets being the USA and Australia. It sells pencils to over 70 countries from Estonia to Korea and Antigua to Saudi Arabia.

'There have been lots of changes during the past 15 years and the rate of change is increasing,' continued Clive. 'As a company, we've never stood still. If you are to remain at the top, you can't adopt a "me too" approach. At the premium end of the market, you have to lead the way with new products and new ideas.'

Artists, animators and architects

all over the world use Cumberland products, and every year around

100,000 people flock to the Cumberland Pencil Museum to learn how it

all began on a misty mountainside 500 years ago

![]()

For further information see