|

CULTURE |

Written and photographed by Dr. Graham R. Lobley

Although the traditional nomadic Bedouin lifestyle is fast disappearing, many of its customs are nonetheless incorporated into modern Arabic culture. Here, we take a look at some classic Bedu traditions and their place in contemporary Arabia.

Inhabitants of the desert

Few places in the desert are capable of supporting the life of even a small community for a significant period of time, hence the Bedouin of Arabia have been constantly on the move. Desert nomads - the Bedouin, with herds of sheep and goats, as well as their prized camels - migrated from one marginally fertile area to another. Each new area offered sustenance and shelter for a limited period, while those left behind were left to regenerate naturally. Bedu, the Arabic word from which the name Bedouin is derived, means ‘inhabitant of the desert,’ and generally refers to the desert-dwelling nomads of Arabia and Sinai. For many, however, the word Bedouin conjures up much more evocative images of sand dunes, flowing robes and camel caravans.

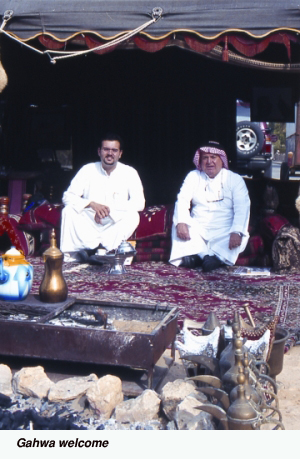

Festivities and hospitality

Visitors to Bedu encampments were traditionally extended considerable hospitality and were also a cause for festivity: including music, poetry, and on special occasions, even dance. The traditional instruments of Bedouin musicians are the shabbaba, a length of metal pipe fashioned into a sort of flute, the rababah, a versatile, one-string violin, and of course the voice. I first heard the distinctive flute-like sound of the shabbaba during a visit to the Malaki Dam in Wadi Jizan. From a nearby hillside, a goatherd was watching over his flock while playing a simple but extremely pleasant lyrical tune.

Bedouin life and desert lore

Inspiration for this article came after a fascinating visit to an exhibition on Bedouin Life and Desert Lore in Dhahran. This excellent and formal exhibition was perfectly complemented by several demonstrations of Bedu crafts and traditions in two tents, the latter extending over several days. These included falconry, rababah music, drinking gahwa, bread making, henna painting and weaving, plus camel and horse rides for the children. Before the exhibition, I was already aware of traditional regional hospitality such as drinking gahwa, Arabic coffee, accompanied with dates. However, I had not realised the Bedu origins of such traditions. Although the classic old black and white photographs featured in parts of the exhibition created a nostalgic atmosphere, there can be no doubt that the Bedu endured a tough nomadic life in such a harsh desert environment.

It was this tenacity and self-sufficiency of the desert dwellers, that captured the imagination and admiration of the major explorers of Arabia’s deserts, such as Lawrence, Thomas, Philby, Doughty and Thesiger.

In a moving passage in Arabian Sands, Wilfred Thesiger (1910 - 2003) wrote:

‘I have travelled among the Karakorum and the Hindu Kush, the mountains of Kurdistan ... drawn always to remote places where cars cannot penetrate, and where something of the old ways survive. I have seen some of the most magnificent scenery in the world and I have lived amongst tribes who are interesting and little known. None of these places has moved me as did the deserts of Arabia.’

He was a skilled wordsmith, and his book became a travel classic in which he vividly described his journeys and surroundings. Thesiger did not seek personal fame and fortune from his achievements in exploration. Instead, he undertook his travels purely and simply because he loved the desert, and because, most of all, he had great respect for the hardy Bedouin, whom he described as the most noble, principled and generous people he had ever encountered.

Thesiger

Thesiger's passion for exploration was fuelled from an early age.

Born in Addis Ababa, the son of a British Minister, he undertook

formative childhood journeys in Africa on camels and mules.

Subsequently, as a young man in Addis, he met Colonel Cheesman,

another famous Arabian explorer, who related the unsolved mystery of

what happened to the Awash River when it flowed into the Danakil

desert. This inspired Thesiger's travels into Danakil country.

There, following the river course,

he ultimately discovered that the

Awash eventually ended in the large salt lake of Abhebad. In fact,

the Danakil salt flats are still used to this day by local people as

an invaluable source of rock salt, which is cut into blocks and

still transported on camel caravans. The Danakil Depression is the

lowest place on earth, dipping to 116 metres, where daytime

temperatures can exceed 50 ºC.

he ultimately discovered that the

Awash eventually ended in the large salt lake of Abhebad. In fact,

the Danakil salt flats are still used to this day by local people as

an invaluable source of rock salt, which is cut into blocks and

still transported on camel caravans. The Danakil Depression is the

lowest place on earth, dipping to 116 metres, where daytime

temperatures can exceed 50 ºC.

Thrill of the unknown

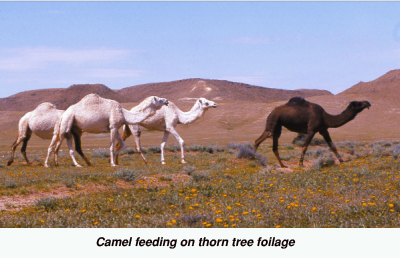

Later work assignments in Sudan also led to further desert treks into the Libyan desert, around Tibesti. Having experienced the deserts of Sudan and the Sahara, Thesiger’s thoughts then turned to the Empty Quarter of Arabia. The thrill of the unknown was missing in the Sudan and when the opportunity finally arose, he embarked on several desert treks in Arabia during 1945-1950, which included two crossings of the Rub'al Khali (Empty Quarter). Thesiger related that in Arabia, the Bedu rode female camels, which also provided milk, whereas in Africa, bulls were usually used, as they could carry heavier loads. The camels on his Arabian treks were never fed, but instead browsed on whatever grazing could be found, including the leaves of thorn trees, managing to eat them with apparent impunity. In his preliminary desert sortie from Salalah, Oman, Thesiger related that their party only fed well when someone shot a gazelle or oryx.

Hunted to extinction

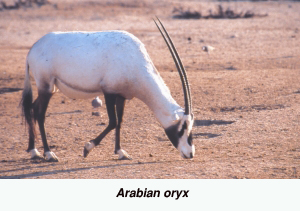

Sadly, only 25 years later, wild Arabian oryx had been hunted to extinction. It was only after an intensive captive breeding programme that wild oryx could once again roam free in larger protected reserves. Around 1800, the Arabian oryx occurred throughout most of the Arabian Peninsula and Sinai. By 1970, it was found only in the southeastern regions of the Rub'al Khali desert. The last one in the wild was shot in 1972. Animals raised in captive populations from zoos around the world were reintroduced into the wild in Oman in 1982. Reintroduced populations now also occur in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, with a total reintroduced population in the wild of approximately 886 in 2003.

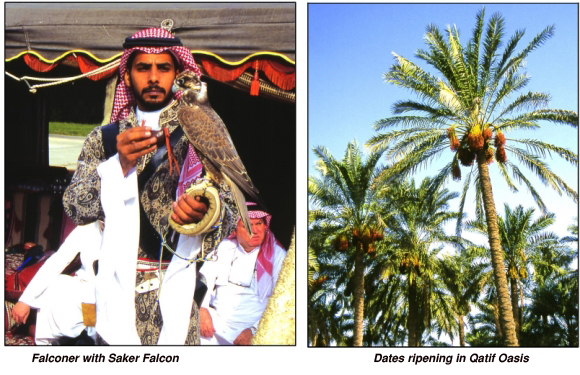

Thesiger was both an Arabist and superb photographer. In his Desert, Marsh and Mountain he showcased some of his best desert photography. The striking photographs of Sheikh Zayid's falconers - especially the falconer on a camel with a peregine - are excellent. Arab falconers often use the saker (Arabic: saqr) but the most prized of all is the peregrine (Arabic: shaheen), the fastest falcon. Falconry was a seasonal form of hunting practiced during the cooler months. Traditionally, Bedu used trained falcons and sleek Saluki dogs to capture prey.

Desert creatures

The primary traditional quarry of Arab falconers is the Houbara bustard, which still migrate across Arabia during the winter months in limited numbers. Falcons will also take hares or rock doves. Due to falconry and predation levels, the Houbara is now threatened as an Arabian breeding species. However, to remedy this, serious conservation efforts are underway in the Mahazat as Sayd Reserve, which we visited in the winter of 1996. There we saw lappet-faced vultures, Arabian oryx and Ruppell's sand fox. The Arabian oryx is an amazing animal, which combines extraordinary beauty with the capability to cope with the toughest desert environments.

Mysteries of the desert

Peoples’ fascination with the desert has continued to this day,

courting more recent photographers and adventurers. Isabel Cutler's

recently published Mysteries of the Desert (2001) features beautiful

and evocative colour images, which illustrate the stark beauty of

the desert and the grandeur of the impressive Tuwaiq escarpment. The

Shedgum escarpment in eastern Saudi Arabia is also another

photogenic desert location, with fascinating wind-sculpted cliffs.

Only the Bedu have sufficient expertise to survive the rigours and

challenges of the desert. Even today, as pick-up trucks replace

camels and nomadic existence is increasingly replaced by city life,

many Saudis cherish their Bedu roots and heritage.

Peoples’ fascination with the desert has continued to this day,

courting more recent photographers and adventurers. Isabel Cutler's

recently published Mysteries of the Desert (2001) features beautiful

and evocative colour images, which illustrate the stark beauty of

the desert and the grandeur of the impressive Tuwaiq escarpment. The

Shedgum escarpment in eastern Saudi Arabia is also another

photogenic desert location, with fascinating wind-sculpted cliffs.

Only the Bedu have sufficient expertise to survive the rigours and

challenges of the desert. Even today, as pick-up trucks replace

camels and nomadic existence is increasingly replaced by city life,

many Saudis cherish their Bedu roots and heritage.

Intriguing designs and patterns

Henna is a cultural artform throughout the Arabian Gulf region, in which people decorate their skin or hair with the rich natural colours of henna. Henna's rich earth-toned hues are widely used to dye intriguing designs and patterns on ladies' hands and feet. Men also sometimes dye their hair and beards with henna. Henna plants are indigenous to the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean. In Saudi folklore, henna designs are considered as good luck symbols.

The backbone of nomadic life

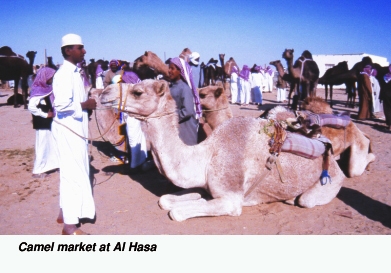

Although camels have been partly replaced by pick-up trucks nowadays, they once formed the backbone of nomadic life across the Arabian and African desert regions.

First domesticated 4,000 years ago by the Arabian frankincense traders, the camel is a truly remarkable animal. Camels were once traded as a kind of currency, for example as dowries and taxes. In cooler months, camels can survive for 50 days without water. Even in summer, they can last for five days without drinking, though they are normally watered every three days. Unlike goats and sheep, camels can graze on thorny desert shrubs, because tough hair protects their lips from injury. Camels are an icon of the desert. Once in the Hejaz Tihama, I noticed the rare sight of several cattle egrets sitting on the backs of resting camels. In Africa, egrets and other birds often perch on game animals, in some cases removing unwelcome ticks and other parasites.

The ideal food

Dates have formed another cornerstone of Bedu lifestyle. Nutritious

and delicious, dates have been cultivated in Arabia for thousands of

years. The ideal food, dates are non-perishable, light and full of

goodness. Even today, dates normally accompany ghawa coffee. In good

hotels and in Saudi Arabian Airlines' premier cabins, ghawa and

dates are served as a classic sign of Arabic hospitality. Date palms

grow naturally, but in the great palm oases of Hasa and Qatif, dates

are produced in vast commercial quantities for domestic consumption

and export. In just this briefest glance at contemporary Arabian

life and culture we thus see how many enduring traditions that are

directly adapted from Bedouin heritage still thrive