|

ART |

|

|

![]()

Written and photographed by Maxine Schur

![]()

![]() eople

have more than just their eyes to see beautiful things with, and

ears to hear beautiful sounds with, and their noses to smell

beautiful smells with. People also feel with their hands and feet.

The flat floor with straight lines is a threat to this sensory

ability, whereas the uneven path is a symphony, a melody for the

feet.’

eople

have more than just their eyes to see beautiful things with, and

ears to hear beautiful sounds with, and their noses to smell

beautiful smells with. People also feel with their hands and feet.

The flat floor with straight lines is a threat to this sensory

ability, whereas the uneven path is a symphony, a melody for the

feet.’

Friedrich Hundertwasser (1928 - 2000)

The most disorienting museum in the world

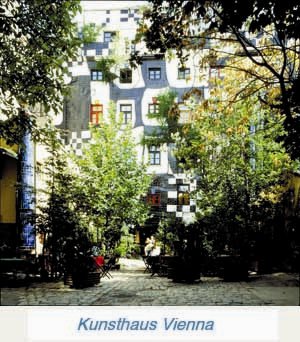

The KunstHausWien in Vienna must be the most disorienting museum in the world. The visitor looks at the floor and sees it rise and dip like sand dunes, while the multi-coloured ceramic pillars tilt dangerously. Yet this museum is a delight: it was designed by Friedrich Hundertwasser - one of Austria's best known and beloved artists and architects.

'The Master’

In Austria Hundertwasser is referred to reverently as 'The Master’ and his museum and the building he designed are important Vienna landmarks, along with the Spanish Riding School and the Schonbrun Palace. At the exhibition, Hundertwasser's shimmering fantasies draw the visitor in, alongside their intriguing titles: Peace Treaty with Nature, Right of Dreams and Flooded Sleep. Hundertwasser was a non-conformist who fought against the dehumanisation of our environment. He celebrated the handmade and the organic, but he also revered that which is childlike and rebellious. Calling himself an ‘architect healer’ Hundertwasser both astonished and delighted his compatriots by turning mundane buildings into colourful toy-like fantasies.

|

|

Rainbow colours

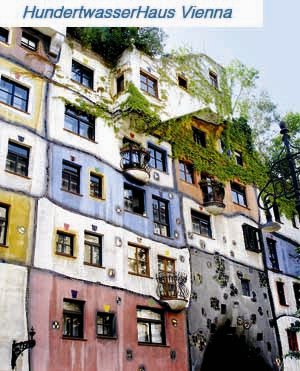

In Vienna, the Spittelau Garbage Incineration Plant, for example, was transformed by Hundertwasser into a psychedelic creation with a dazzling gold tower, while the Bad Fischau Highway Inn, a prefab 1950s diner, 45 miles south of Vienna, is now topped by Hundertwasser's blue octagonal observation tower, which in turn is topped by a live fir tree. The artist also painted rainbow colours on an old twelve-ton freighter which he called ‘Rainy Day’ and which was his second home on the Danube. However, there is no better example of this artist’s bold spirit than at the HundertwasserHaus, a Viennese public housing project he designed in 1983. The HundertwasserHaus was actually a rather dreary grey-brick apartment building until Hundertwasser decided to ‘return dignity to the dweller’ by redesigning it inside and out.

Circus clowns let loose with giant crayons

Observers

have remarked that Hundertwasser buildings look as though circus

clowns have been let loose on them with giant crayons. At just about

any time of day, the sidewalk opposite the Hundertwasser apartment

building will have one or two people admiring the blue, orange,

yellow, white and brown walls, and the wavy roofs which have been

planted with mini-meadows and crowned with gold onion domes.

Concrete arches have been decorated with unevenly distributed mirror

fragments and multi-coloured tiles that float over the walls like

party streamers, along with the hundreds of gaily painted windows,

so small and unexpectedly placed that they look like a stamp

collection ornamenting the building’s lines.

Observers

have remarked that Hundertwasser buildings look as though circus

clowns have been let loose on them with giant crayons. At just about

any time of day, the sidewalk opposite the Hundertwasser apartment

building will have one or two people admiring the blue, orange,

yellow, white and brown walls, and the wavy roofs which have been

planted with mini-meadows and crowned with gold onion domes.

Concrete arches have been decorated with unevenly distributed mirror

fragments and multi-coloured tiles that float over the walls like

party streamers, along with the hundreds of gaily painted windows,

so small and unexpectedly placed that they look like a stamp

collection ornamenting the building’s lines.

Tree tenants

On the cornices, windowsills and gables of the apartment, rise an odd assortment of ornaments: bright yellow bowling pins, Greek figures, lions, red Santa hats. And as if all this were not enough, trees sprout from the windows. These ‘tree tenants’, as Hundertwasser calls them, exemplify his philosophy of returning greenery to the city. The tree tenants cleanse the air and purify the water as part of their ‘rent’.

Manifesto of Tenant's Rights

Hundertwasser wrote numerous manifestos arguing against drab colour and the ‘straight line’. In one, called The Manifesto of Tenant's Rights, he reveals his idiosyncratic philosophy:

Renters must be able to lean out of their windows and scratch off all the plaster within reach. And they must be permitted to paint everything pink within reach of a long brush so that it can be seen from a distance, from the street, that a human lives there!

The ‘Adventure Room’

If the exterior of the HundertwasserHaus gives Gaudi a run for his money, the interior is just as fanciful. The staircase weaves around, as in a fun house. The trail to the apartment house caf... leads over pieces of stone, while a play centre, called the ‘Adventure Room’, has a floor that not only sports a window, but undulates so much that kids use it as a slide - when they're not drawing on the walls, as the Manifesto declares:

‘Children must be able to scribble, paint and scratch all public walls as high as their arms can reach.’

Pelicans, cacti and butterflies

Wildly painted bathrooms abound with pelicans, cacti and butterflies and the ‘tile graffiti’ of the individual tile. Even more curious, each bathroom has an elaborate toilet flushing system by which the occupants must flush their empty toilets a required number of times a day to water the ‘tree tenants’. Some of the captivating features of this unique dwelling are: walls that roll in and out like sea waves, an underground garage where each parking space is marked by a different flower mosaic, and coats of arms from demolished buildings.

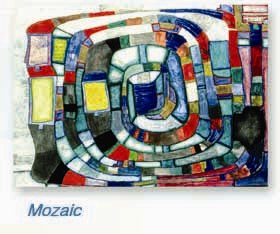

Eastern decoration, luxurious colour and rich texture

If HundertwasserHaus whets your appetite for more things wild and witty, then try the KunstHausWien, Hundertwasser's four story museum dedicated to himself; just two streets away. Unconventional, just as the apartments are, the museum also houses temporary exhibitions and serves as a gathering place for artists. The first floor holds a spectacular joyous mural. Hundertwasser's paintings are characterised by Eastern decoration, luxurious colour and rich texture - paintings that seem influenced both by Austrian Baroque and Vienna's early-twentieth century Jugendstil artists such as Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele.

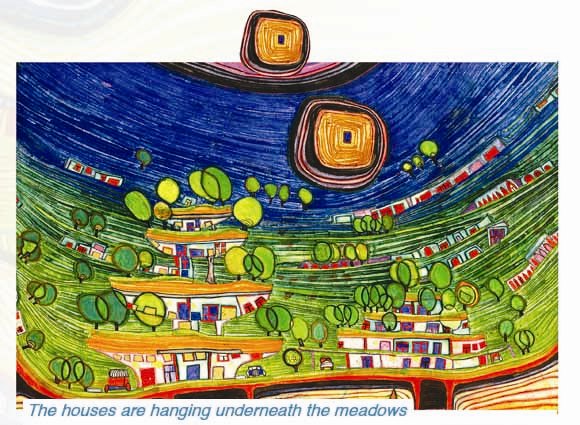

Hundred Waters

Born in Vienna in 1928 as Friedrich Stowasser, the artist, at the age of 22, gave himself the name 'Hundertwasser’ (Hundred Waters) and had his first exhibition in Paris. Early on, architecture played a large part in his paintings. He looked at its relationship to human welfare and the dignity of life. One of his best known paintings The Houses are Hanging Underneath the Meadows conveys the idea that the ‘horizontal belongs to nature; the vertical to man’. The picture shows a building planted with gardens and a building with each floor and roof turned into a meadow. His idea was that if humans were to build like this, an aerial landscape would show an unaltered terrain with every horizontal surface planted with greenery. Protesting against the greyness of most architecture, Hundertwasser's paintings show worlds that contain hundreds of colours; he believed that diversity of colour is symbolic of a higher level of being.

|

|

Japanese master woodblock printers

In the early 1960s Hundertwasser collaborated with Japanese master woodblock printers in Tokyo, and learned to employ traditional Japanese perspective and calligraphy in his works. Eschewing store-bought paints, he made his own by grinding together inorganic materials: bricks, volcanic sand, earth, coal, and white lime, then mixing them with egg or acrylic or wax. The result was paint that was rougher in texture and that contained what he called ‘more soul’.

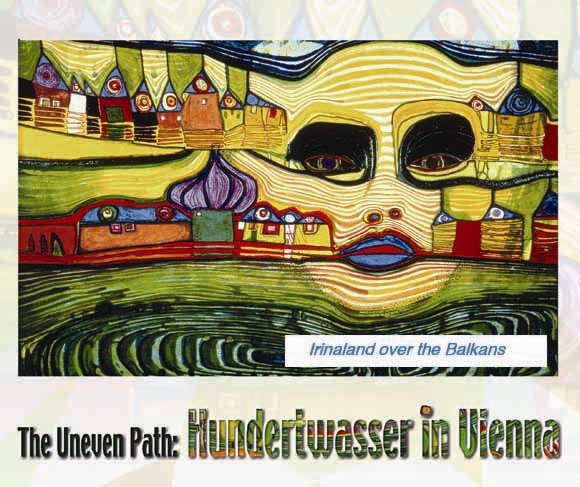

Phosphorescent and fluorescent colours

In the late 1960s, he introduced into graphic printing the use of phosphorescent and fluorescent colours as well as metal embossing, techniques which have now become his signature mark. Hundertwasser used these techniques to the utmost in one of his most famous images, Irinaland Over the Balkans (1969). The image shows a woman's face floating over the countryside, her omnipresence symbolising a memory of love. This print not only pushed the envelope of the printing process at the time, but must have also pushed the printer to the point of a nervous breakdown, as 31 colours had to register perfectly, with two of the colours being phosphorescent so that Irina's eyes would shine.

Egg tempera coloured with brick dust

Because Hundertwasser believed that even prints must be ‘original’, he painstakingly primed each sheet with egg tempera coloured with brick dust. He applied this with a palette knife to the sheet before printing, such that many of his lithographs are in actual fact both a print and a painting. This method was no small feat, for example Good Morning City was produced in a run of 10,002 - with each sheet being different from every other.

|

|

Positive, free, romantic, beautiful...

Surrounded by wide black mats and deep black frames, and strategically spotlit, the pictures appear to float in space. The effect is dramatic. The pictures gleam and glitter. Their dazzle is no accident for Hundertwasser believed that the arts should be positive, free, romantic, beautiful, something like a jewel.

A fairy-tale resort

The top floor has yet more drawings and a garden fountain that recycles its own water. There's also a display of the flags Hundertwasser created, as well as the stamps he designed for Senegal and the United Nations. Here too, you can see the models and designs he created for a host of other buildings, such as the grain silo of Krems, the Rupertinum Museum in Salzburg, the Rosenthal factory in Self and the Beaux Arts Museum in Brussels. One amazing design is a fairy-tale resort that opened recently in the small town of Blumau, an hour and a half’s drive south of Vienna. Called Rogner-Bad Blumau, this spa-resort bills itself as ‘the world's largest habitable work of art’ and features Hundertwasser's signature design elements - undulating walls, bright colours and onion domes - as well as golf, swimming pools and a variety of health treatments.

A world apart

The museum gift shop is filled with Hundertwasser objets d'art, both kitschy and classy. Here one can buy Hundertwasser umbrellas, earrings, necklaces, mugs, scarves, pens, puzzles, postcards, calendars, key chains, tea sets and ties. Once outside the museum, the visitor is abruptly back in the city streets lined with Hapsburg-era houses that now seem grey and sombre. There's no doubt about it, the museums of Hundertwasser are a world apart

Seeing Hundertwasser's art

The KunstHausWien is at 13 Untere Weissgerberstrasse and is open

from 10.00 am to 7.00 pm

![]()