|

EXPLORATIONS |

![]()

Written by John Pint

Photographed by John and Susy Pint

![]()

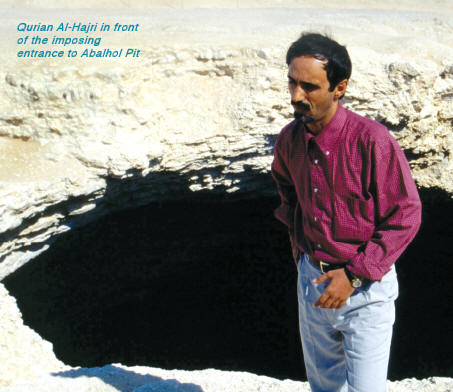

Some time ago, a road builder for Saudi Aramco, named Qurian Al-Hajri, was driving through a flat, featureless, hard-pan plain somewhere west of Saudi Arabia's Ghawar oil field, the largest of its kind in the world. Suddenly, an enormous hole appeared before him, almost out of nowhere and by the time he put on his brakes, he was only metres from the edge of a great pit, so deep that he could not see its bottom. Realising the serious danger this wide cavern mouth represented for anyone crossing the desert on four wheels, Al-Hajri immediately arranged for a rampart of dirt to be erected around the hole.

Forget using GPS

Years later, the story of Qurian Al-Hajri's encounter with this formidable pit reached our ears: many people in Saudi Arabia knew that we were interested in exploring caves; the deeper the better. Having discovered his office phone number, we decided to give him a call. "We heard about the huge pit you found in the desert. Do you have the GPS co-ordinates?" "I am a Bedu," he replied. "I don't need GPS. Aramco gave me one, years ago, and I put it in a drawer where it still lies. But I'd be happy to meet you and take you to the hole." We immediately contacted our caving friends and began planning a visit to Qurian's abyss.

|

|

A pea soup fog

So it was that one very cold day in December we found ourselves driving from Al Kharj (just south of Riyadh) toward a GOSP (Gas Oil Separation Plant) not far from the lonely outpost of Al-Haradh. My wife and I had spent the night shivering in our little tent only to be woken at sunrise by an interminable procession of heavy vehicles lumbering along the network of rig roads that crisscross the Ghawar oil field. When we poked our heads out to see what was making all the commotion, however, we were amazed to find ourselves surrounded by a wall of white. A pea soup fog was the last thing we had expected to encounter in a desert!

A Christmas tree with a difference

Precisely at 10 a.m. our colleagues, Mike Gibson and Arlene Foss, pulled up next to us and a few minutes later, a white Explorer appeared. "Kayf al hal? (How are you?) I am Qurian. Nice to meet you. Yalla, yalla! (Let's go!)," said the wiry man inside. Qurian led us through a maze of graded Aramco roads, stopping occasionally to show us what the oilmen are doing in the area. "This pipe with all the valves on it is called a Christmas Tree. Oil was found here long ago, but only recently did we open the valves to let it out. Now it's flowing through this pipeline. Can you hear it?" The pipe was humming, and hot to the touch. In Saudi Arabia the problem is not pumping the oil out, but keeping it in.

|

|

|

Qurian, the Bedu Beyond the oil field lay the empty desert whose most salient feature was the lack of any feature. There wasn't even much sand to be seen, just a hard, white, flat surface that stretched off in every direction. Again I asked Qurian why he didn't use a GPS. "Now, I am very sensitive to the smallest details of my surroundings," he replied. "I have to keep myself razor sharp. If I used GPS, I would lose my edge." Curious about this man's outlook, we asked Qurian how much of him was Bedu and how much Aramcoan. "I am doing all I can to keep up the way of life I was taught as a child. It was a hard life and it made me strong. But today, people have it easy and as a result, they are becoming weak. So, I don't live in Aramco housing - I live in a black, goatskin tent that was hand woven by my mother, in the same lonely spot where my grandfather dug a well long ago." |

|

|

|

|

A bottomless pit

About 20 kilometres into the desert, the dull white of the landscape was broken by a circle of deep green. It was a round wheat field irrigated by a slowly rotating water pipe. This was obviously the landmark Qurian had been looking for. "The big hole is out in that direction," said Qurian through the open car window, pointing west. And off we went, our cars, three tiny specks on a vast white sheet, bright and glaring in the afternoon sun. For most of the 50 kilometres I could not distinguish any feature that might help Qurian orient himself. How did he do it?

A half hour later, we saw a low, dirt rampart breaking the monotony of the flat plain. Standing on top of the rampart, we looked down into the mouth of a huge hole, a great, black scar contrasted against the shimmering white of the desert. No bottom could be seen. Mike and I had figured the hole would be 30 metres deep at the most. Now we were glad we had several hundred-metre ropes along. While we circumnavigated the irregularly shaped chasm, looking for a good rigging point, Qurian pulled out what looked like a briefcase and turned on a satellite phone which he used to contact his headquarters. "Even though we're fasting for Ramadan and our office hours are up, I'm always getting calls. Aramco never stops," he explained.

|

|

The Father of Fear

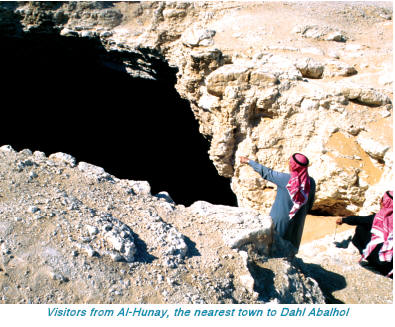

Then, out of nowhere, a pick-up truck appeared and out stepped several bearded gentlemen wearing dark, winter thobes. They were from Al-Hunay, about 30 kilometres away and probably the closest settlement to this hole. They seemed delighted that we had come 'all the way from Riyadh' just to visit this unusual spot. "We call this Dahl (Cave) Abalhol," they told us, "because it's BIG!"

"What does Abalhol mean?" we asked. From their and Qurian's explanation, we gathered that Abalhol was the name of a "very large and very ancient Egyptian." Only later did we learn that this old Egyptian giant is actually the "Great Sphinx of Giza" and Abalhol is short for Abu Al-Hol, meaning Father of Fear.

After a while, our visitors left, including Qurian, who urged us to visit his tent at Ain Dar, where he had "one hundred camels". He suggested my wife would enjoy milking them; we both, however, knew otherwise!

|

|

Into the throat of Dahl Albalhol

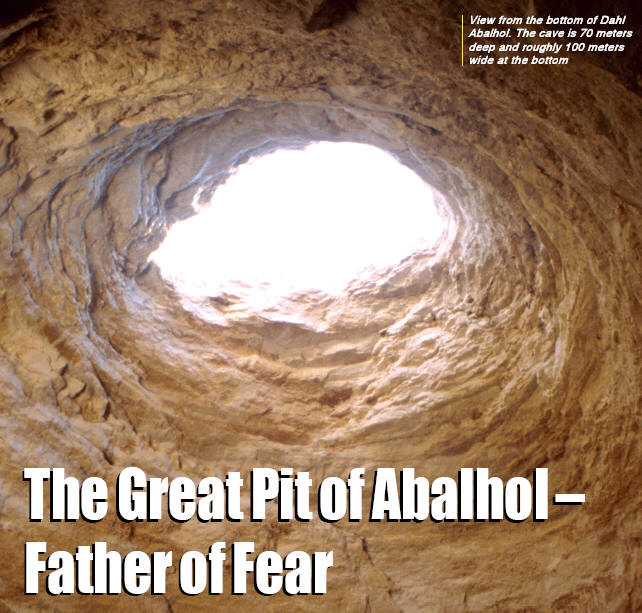

We then went to take a good look at the pit. The mouth was 20x30 metres and a string lowered to the bottom indicated it was around 70 metres below us. This suggested that Abalhol might be the fourth deepest cave in Saudi Arabia.

We connected two ropes to one of our vehicles and then threaded the ropes through the bars of our 'racks' - friction devices attached to our harnesses, permitting us to slide down the ropes slowly. About ten metres below the surface, Abalhol opens up into a huge, fully illuminated single room, which gives you the feeling that you are hanging in space, maybe the way you would feel if you were suspended from a helicopter over an enormous canyon. As we dropped into the pit, we found ourselves among hundreds of rock doves soaring across the vast room, which was almost perfectly round. We landed on the steep hillside at the bottom and scrambled down to where we could gaze at the huge dome above us without fear of being hit by debris from above. It was a spectacular sight.

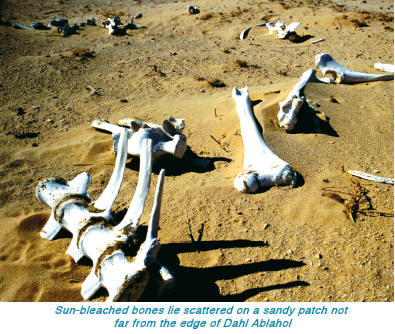

About half the cave can easily be reached by walking around the perimeter. The rest is covered by giant blocks of breakdown that looked very unstable. We moved along, looking for passages, but for the most part only succeeded in surprising the many doves that were blissfully roosting on the floor. These birds would inevitably pop up right in our faces, scaring us as much as we scared them. Other features at the pit bottom included truck tires, sand-filled soda bottles and the corpses of numerous dehydrated doves.

|

|

Return to the surface

Having found no significant passages or formations and having thoroughly worn out our welcome with the doves, we prepared our return to the surface. For this we used mechanical ascenders; these slide up the rope easily but hold tight when pulled downward. As I prepared for my climb, I saw Mike stuffing our various bags of photo gear and such into a giant duffle bag.

"Mike, that looks like the Abalhol of all gear bags. Shouldn't we send up one bag at a time?" "It'll be a lot easier to do it all in one haul," were Mike's last words on the matter as I started up the rope, and unforgettable words they proved to be. By the time both of us got out of that hole, darkness was fast approaching. "Quick, let's get the gear bag up while we have light," I said. Mike leaned over the edge of the great pit and tugged on the rope. "I can't even budge it. Guess we'll have to rig a pulley system." To cut a long story short, it took us another two hours to haul that heavy bag up and over the lip but when we did it, we declared ourselves qualified and ready to pull the fattest camel in the Kingdom out of the deepest pit, as long as nobody was worried about how long it might take.

As we walked back to our tents a full moon

rose into the sky, lighting up the desert all around us and casting

spooky shadows deep into throat of Dahl Abalhol. At that moment it

truly deserved its name Father of Fear ![]()